Was Coldplay Ever Cool?

an ode to long-forgotten middle school favorites

Image: screenshot from the music video for Viva la Vida (Anton Corbijn Version).

In middle school, my favorite bands were Coldplay and Songs: Ohia. Molina’s work has stood the test of time, and I often find delicious enjoyment in my college-aged friends finally discovering his stuff. None of us are “I liked it first” hipsters, and so it feels like I’ve been living at the musical El Dorado all these years, preparing my home for a long-awaited visit. College is about the right time for Molina’s discog, though, and their response to “he was my favorite artist in middle school” is usually something like horror that I found Lioness a soul balm at the tender age of 13. So it goes.

If Molina is my shining castle in the sky, Coldplay is the Castlevania skeleton-boss in a closet. The first few times I disclosed the weighty sin of having liked Coldplay in middle school, I felt like I was Raskolnikov confessing to axe murder. Inevitably, though, the other person’s response baffled me more than outright mockery. “They’re pretty good” or “I like Viva la Vida” or something else like that. Each time, it left me more perturbed than if they had taken the bait and made fun of Coldplay with me. The basic question I was left with was: Why am I the only person who knows that Coldplay is lame?

Answering the question turned out to be harder than I thought. It felt obvious to me that the general consensus was that Coldplay was mediocre, cringe, early-2000s hogwash with all the continued relevance of R.E.M. But that gut feeling about the zeitgeist turned out to be impossible to confirm. It’s easy to point to plenty of other people who don’t like Coldplay…

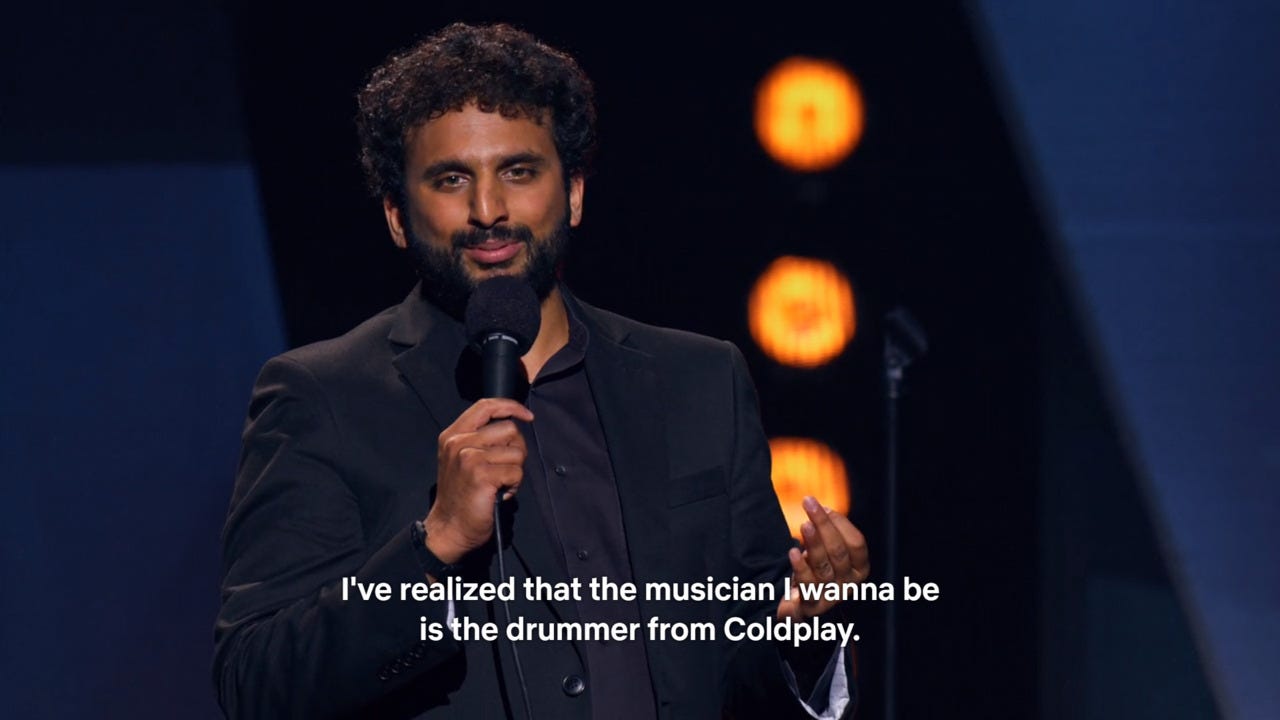

Nish Kumar’s bit continues, “I wanna be the drummer from Coldplay so bad, ‘cause that dude’s rich as shit, and no one knows who the fuck he is.”

… but then again, the Internet might as well be an index of people who don’t like things. If I wanted to make a statement about the zeitgeist, I would be forced to concede that Coldplay’s 2021 album hitting the top of the Billboard Charts counts for a bit more than someone taking the piss.

Is the issue that they’re popular? As aforementioned, I’m not really that type of snob. Pop musicians have different artistic visions than indie singer-songwriters, and aren’t ontologically worse for it. SOPHIE said that portraying happiness in music is as worthy a pursuit as portraying sadness, and Leonard Cohen said that popular music’s purpose is to unite us and make background music for our lives, and I think they’re both right. The fact that I’m a mopey bastard who listened to Jason Molina at 13 doesn’t mean that Chris Martin is a hack, just that the world is bigger than my tastes.

Coldplay should be judged by Cohen’s metric rather than Pitchfork’s. And by the volume of people willing to buy their concert tickets, it’s easy to think that being able to name a drummer doesn’t matter. How many people have cried to Fix You, danced to Something Just Like This, or made TikToks set to Yellow? It’s undeniable that they’re good at what they do, and their sales reflect it.

I’ve heard Coldplay described as a “bar band,” but when my friend played in a bar, he apologized after telling me the cover charge was $15.

All the same, I couldn’t shake the feeling that they were deeply cringe. And so it seemed like my issue might just be that I don’t like Coldplay. Plenty of people grow out of their middle school favorites, with no deeper meaning than adolescent ego death behind it. So, the next step in my investigation was revisiting the parts of their discog I liked as a kid, in incognito YouTube tabs to avoid messing up my last.fm. But I discovered quite the opposite.

I mean, I wouldn’t buy a ticket, but I wouldn’t turn down free ones, either. Several tracks from A Rush of Blood to the Head got stuck in my head, and I found myself scouring Spotify for suitably cool covers to add to my playlists. I never found any. Since my loophole for listening to Coldplay without scrobbling it failed,1 I returned to that incognito Youtube tab again and again, with all the shame of an actual axe murderer.

In the comments were scores of people corroborating my earlier findings. They talked about how much they loved Coldplay’s music, the fond memories they had of Parachutes and X&Y, and how only cool kids like us still listened to Coldplay in 2023. Sampling bias, to be sure, but I couldn’t avoid the fact that I had circled back to my original question. Why am I the only person who knows that Coldplay is lame?

My new plan of attack was simple. Since I couldn’t rely on an aggregate of everyone else’s opinions, I analyzed Coldplay’s lyricism, using the poetry analysis skills I learned in college. The logic here was that there must be some hidden gem of antithesis that explained what made my own antithetical love-hate for them tick.

But the main discovery was that Chris Martin might have gotten a generous C- in my professor’s poetry class. Antithesis and irony and implication — more popularly known as “lying” — did not feature in his writing. Instead, the songs mostly stated how he felt, maybe with some fun metaphors and sparse instrumentation to send the point home. Working in tandem with his band members, the emotional impact landed. Taken as poems, though, the chapbook could use some work.

As an offshoot of this exploration, I started listening to Coldplay with some regularity. It was still on YouTube, where only the algorithm would know my sins, and therefore punish me appropriately with Snow Patrol recommendations. Crucially, it also wouldn’t affect my Spotify Wrapped, and my friends wouldn’t be able to see that I had listened to them. (The fact that those same friends had told me they liked Coldplay didn’t factor into my reasoning.)

This did strike me as irrational, especially when I switched from premium Spotify to be bombasted by ads on YouTube, just to watch the same Fix You lyric video I watched ten years ago. Still, it felt impossible to publicly listen to Coldplay, even if nobody would notice or care. That same Raskolnikovian fear came back to me every time I tried to hit play on Spotify, irrationality be damned. Even if my friends weren’t going to make fun of me, even if no one cared. I still somehow knew that I was about to commit a sin of Style and Taste. No matter what others thought, no matter how many glowing reviews of Coldplay’s music I read, or what I found out for myself, I still found in the privacy of my own mind that I was being cringe.

I have tried, over and over, to write this essay. The issue is that it’s subjective, and subjectivity and I are acquaintances at best. I know it in passing because it comes up often in my studies – you can’t really be a historian or a writer or translator without bumping into it from time to time. But all the same, I have gained a certain distaste for it, in the same way a classmate might become a nemesis through a turn of phrase too annoying or a garish scarf worn too often. I may hate from afar, but subjectivity has no idea I exist. Subjectively, I am an aberration, a face in a sea of faces, a nothing.

Is that the issue, then? Anonymity? It’d be nice to think so, anyway. Then my issues are surmountable, through notoriety or just plain ole success, and there will be no lingering resentments. We can greet each other as old chums, resentments forgotten, because subjectivity has been forced to yield to the objective fact that I am known, that I am read.

But writing that sentence, even with my eyes clenched shut and my fingers flying over the keyboard, is difficult. Anonymity has nothing to do with it. Actually, it’s a secret third thing, totally detached from the sliding scale of love and hate. Subjectivity is the perfect chink in the armor of irony. No matter how many things I sacrifice to become cool, suave, and post-post-post-post ironic, subjectivity will always beat me. There will always be someone to say, “Nah, that whips ass, actually.” Or, more acutely: “No, you’re wrong about that.” “No, this isn’t good.” “No, I don’t like this essay.” (Stop reading, then!) Objective coolness relies on absolute defensibility, and, failing that, absolute willingness to abandon anything. And it always fails that, thanks to our old friend, the garish-scarved subjectivity.

I put my jokes in parentheses, and it becomes easy to miss that they are the point. Stop reading, then! I don’t need to stop writing. Even now, I am afraid to say what I mean with my chest. It’s so easy to joke. If I smother my real thoughts in irony and self-loathing and parentheses, then I am finally safe. I am finally draped in the shining armor of irony, which can twist even subjective arrows away from my beating heart. And I have nothing left to show for it. No ideas, no writing, no soul. My safety has cost me my life.

So the only choice left is to be vulnerable. Only through vulnerability can I make it out of this world alive. Otherwise, I risk being strangled to death by my own hands.

After a while of analyzing their lyrics, I found the problem with Coldplay.

Or, at least, what made Coldplay an a good scapegoat to redeem me at the altar of objective taste: earnestness. The lyrics lack antithesis because Chris Martin never felt a need to wear that ironically shining armor. To someone in the late stages of irony toxicity, it’s difficult to accept someone saying that they really do like something. It becomes all the more cutting because you’ve sacrificed that very ability to be earnest in the name of self-defense.

A part of me is tempted to blame this on the Internet, because it’s easy. Constantly being a click away from awful opinions changes your mental landscape on some level. But it doesn’t really matter where an issue like this comes from. It is societally transmitted, but individually cured. I could sit around caterwauling all day about how the Internet killed my first musical love, but that won’t bring it back. It won’t make me less irony-poisoned, or make me less likely to pass on those noxious thought patterns to someone else. Learning who I was before then is the only path back.

In the months since I started writing this essay, I’ve made a small triumph over myself. My Coldplay listening, though still rare, now happens on Spotify, where my friends and last.fm can take note of it to their heart’s content. At first the discomfort was almost too much to bear, and I had to fight the urge to either delete the scrobble or joke about it, and so make penance for my bad taste. I did neither, and over time it stopped seeming like some grand crime, risking the punishment of being given a one-way ticket back to middle school. Absolutely no one has commented on it.

That’s probably true of your middle school favorites, too. Nobody cares as much as you. Shame and its pantheon of related emotions are, too often, burdens we put on our own backs. Sometimes that’s good, but when it comes to artists you used to love, it’s a burden you should drop.

And even if they are actually cringe, you might be happy you revisited them. Just for the memories.

I didn’t know at the time that you can simply delete scrobbles, which would have saved me a lot of trouble.

This makes me want to listen to that Chumbawumba album I loved in middle school. Saw one of your stickers out in the wild in Northside and followed it here :)