Captain, we've got a breech!

Fluidity in dress is hardly new.

Illustration: Endika the Pirate Princess by Sasha Beliaev.

Warning for a quoted source using intersexist language.

As of late, I have been researching Venetian 16th century dress with the aim of maybe making a costume. In this endeavor, I was delighted to find several drawings of women wearing breeches under their skirts- validating several pieces of fantasy art I enjoy.

Left: “Diversarum nationum habitus” (1594), via Bonhams. Right: ibid., via the Victoria and Albert Museum. Both are labeled “Venetian Courtesan” in Latin (though, admittedly, a medieval Latin which scans at first pass as Italian).

I was less delighted to see comments along the lines of “how do you know they're breeches and not drawers?”

This is technically an innocuous comment, but it frustrates me because the sentiment behind the comment is a discomfort with gender fluidity/crossdressing. It is also rather foolish if you analyze the appearance of these garments and compare them to drawers. Drawers are, simply, underwear. Because of this, they have a few common features.

Drawers typically cover the legs, hips, and rear.

Drawers made to go under dresses most often have a split crotch, not a seamed crotch. This is because they are often worn under multiple long skirts and are hard to quickly remove when you need to go to the bathroom. Drawers that go under breeches/hose do not necessarily have this, as they lose any convenience of the split, with the added issue of effectively going commando despite wearing underwear.

Drawers protect your nice outer clothes from your dirty, sweaty, yucky flesh. This means they get pee, sweat, dirt, blood, and excrement on them. As a result, they get washed often, and since washing was often incredibly rough, they were often made of linen.

Slashes were acceptable for the nicer outer clothes, but not a good idea for underwear. In particular, slashes tended to rely upon the weave of the fabric to prevent fraying, and were not finished. Further, while embroidering underwear was certainly common, there tends to be specific formats the embroidery is done in, likely influenced by which sections of the garment would be most abused during wearing and washing. For drawers, embroidery tends to be around the waist and the bottom of each leg.

Let's compare these characteristics against our breeches, shall we?

First, while we have a few drawings, we only have one surviving pair of breeches that I know of, from the Museo del Tessuto, Prato. They are made of linen with blue silk embroidery covering every inch of fabric. In addition, they have a fixed waistband and are not split crotch.

These, I will grant, are somewhat dubious. There are a few Italian drawers from a similar era that are also not split crotch; however, one of these is possibly made for a man as it was a part of a set that included men's garments. The other pair of drawers does not have a reason behind its identification as possibly being for a woman.1 We are almost certain the breeches are a woman's in part because the extensive embroidery contains the refrain “I want his heart”, repeated over and over. It is unlikely a (cis) man would have either spent the time required to create such a garment, or had one commissioned. Another difference between these two drawers and the breeches are the bottom hems; the breeches are gathered to a band which can be tied around the leg, and the drawers are straight without a band. Additionally, other pictures of these breeches show a lining, a very strange choice for underwear; chemises with heavy embroidery have no mentioned lining in my experience.

The other breeches are visual depictions. Some of these are straight legged and plain, one is gathered and round (this example is also colored, showing us the breeches are of pink fabric- an unusual color choice for drawers, and featuring heavy embroidery in gold that would be an interesting choice for underwear), but two examples are slashed. As stated before, slashing was typically not finished to prevent fraying. These are similar to depictions of the breeches worn by men in Venice in the same time, and indeed this style was exported and known as “Venetians” in other parts of Europe, such as England.

In text, we have an official complaint from 1578 regarding courtesans in Venice dressing as men. According to Vecellio circa the 1590s, “public” prostitutes (a lower class than courtesans) typically wore masculine clothing, including (French style) men's vests, shirts, and breeches. He claimed breeches were an easy identifier of a prostitute.

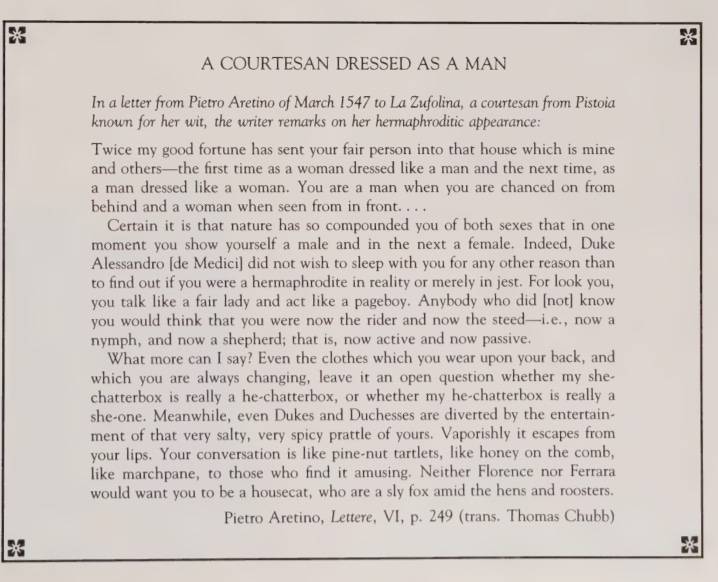

From Lynne Lawner’s “Lives of the Courtesans.”

Pietro Aretino, from another part of Italy in the 1540s, similarly remarked upon a prostitute he knew who dressed as a man and acted androgynously2. His remarks are quite interesting in light of biographical information about himself: he was a self identified sodomite, and wrote several plays and poems with queer themes. There is some indication he had an interest in women3, but his preceding remarks will strike trans readers as very… familiar. I have no desire to debate La Zufolina's gender in specific today, but Venice partially promoted prostitutes (who again, wore breeches and could even be identified by them4) to curb “sodomy”, specifically male-male5. This is something which we as modern viewers have described as trying to “turn” them, but is this truly so? After all, these people fooled no one; but, could they have been performing gender, through clothing, in a way normally unacceptable and inaccessible to their time? Are we seeing only women adopting men's clothes, as many prostitutes surely were women- or are we seeing a mixed crowd?

Our breeches are commonly associated with Venetian Courtesans, but were not exclusive to Venice or Courtesans. Eleonora of Toledo owned a red taffeta pair, and Maria de Medici owned several of gold brocade. Both women were connected to Florence, and were not courtesans. Courtesans often adopted masculine dress elements6, but this was common to other women of the era in certain contexts. By the mid to late 1500s, women often wore doublets- originally, a masculine garment. Alcega's rare patterning book from the era gives diagrams of both garments, which are remarkably similar. The main difference is the woman's pattern does not have the “peascod” belly, a deliberate exaggeration of the lower stomach fashionable for men at the time7. Additionally, Marguerite de Navarre, a French princess, was known for masculine dress, though I have not seen mention of her wearing breeches8. Masculine and feminine dress have never been so neatly separated as they initially appear.

Elizabeth I in her most famous portrait wearing a “rather masculine” doublet, via the National Portrait Gallery.

I have seen it suggested that these were an adoption of Islamic women's dress, but I consider this somewhat unlikely as the pants worn in the Islamic world typically fastened by drawstring. This feature was culturally rather significant, and the drawstrings themselves could be elaborately decorated and exchanged as love tokens9. The breeches, from what I can see, are not made with drawstrings. However, Islamic women's pants do typically lack a split crotch. I will not rule out the possible influence, but I think if this is so, it influenced both men's and women's breeches, and was likely a more generalized Islamic dress influence as the pants worn by women and men were similar. Therefore, we can be relatively certain these articles are not drawers, but breeches.

Janet Arnold, “Patterns of Fashion: 1560-1620,” 4.

See also Lawner’s “Lives of the Courtesans.”

https://rictornorton.co.uk/aretino.htm <- guy apparently put his whole book online and this section is about our guy

Perhaps being distinguished from ladies who picked up the style by not hiding them, as one illustration of a prostitute in a see through skirt shows.

Lawner, “Courtesans.”

Moda a Firenze 1540 - 1580 as translated and quoted by Patterning Italian Renaissance Gowns: Focusing on Florence and Venice (1480 – 1530) by Maestra Suzanne de la Ferté

Arnold, “Patterns.”

Lawner, “Courtesans.”

Arab Dress: From the Dawn of Islam to Modern Times by Yedida Stillman

fierce