Against "Against the Torment Nexus"

In Defense of Dystopia

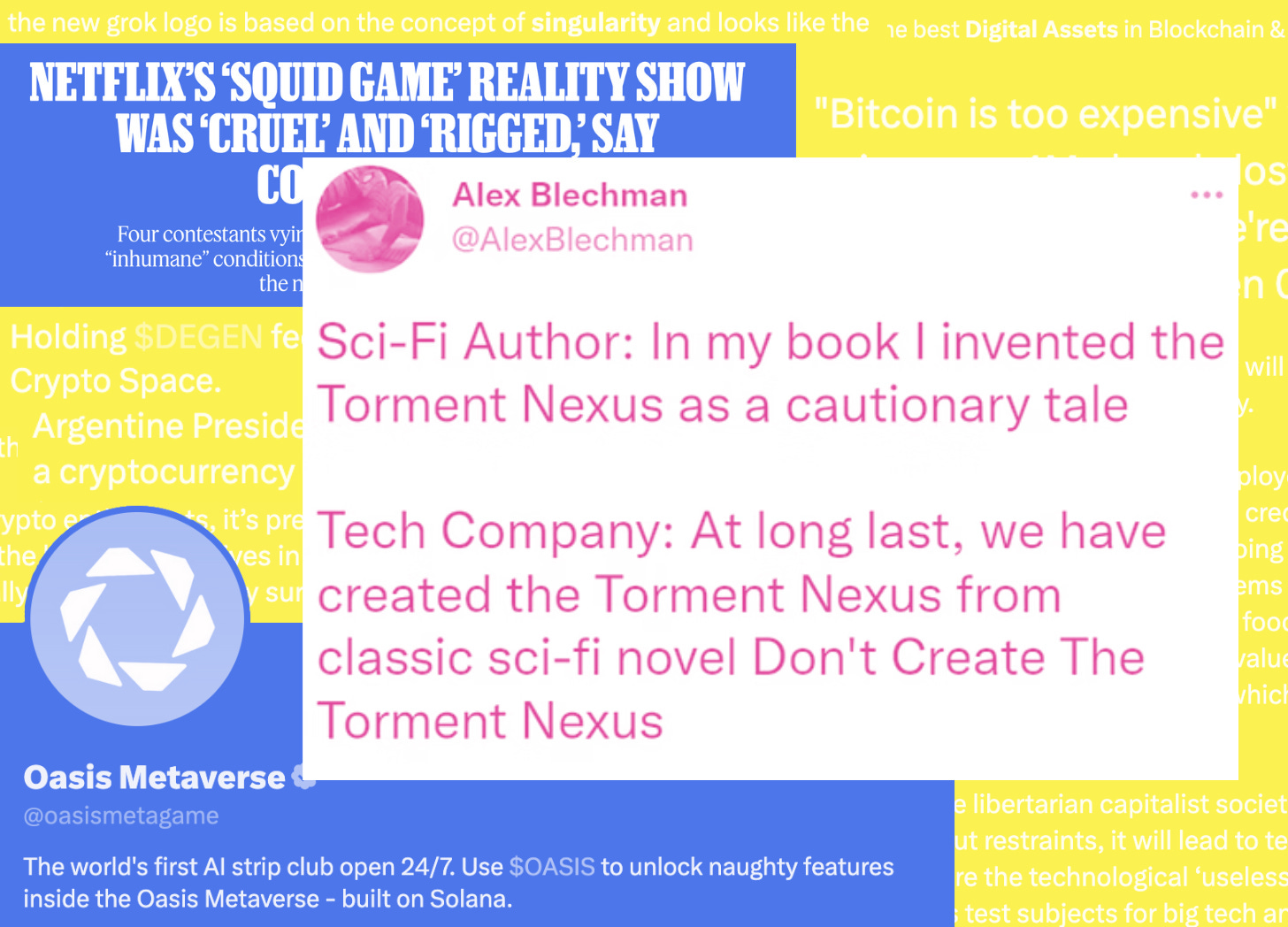

I’ve been shadowboxing Zeke in my mind since he posted Against the Torment Nexus a couple months ago. In it, he suggests that the “Torment Nexus” phenomenon applies not only to hard tech, like AI, but also to the social systems and environments of dystopias. Hal is a Torment Nexus, but so are The Hunger Games. I’d be all for that, except then he argues that sci-fi has “grown out of” dystopia. Narrativizing any subject matter inherently glamorizes it, so can the author of Don’t Create the Torment Nexus be surprised when Zuckerberg creates it? Can we be surprised at the multiple productions of Squid Game In Real Life?

Now, the obvious argument here is that it’s not an author’s fault if their story is misinterpreted, and that fear of misinterpretation should not determine what an author writes. However, can we take that stance while still believing in the value of representation? In the power of a story to shape reality?

Also… they’re pouring billions of dollars into making Squid Games in real life. When the point of dystopia is missed so often and so obviously, we have to reckon with that.

So – does the creation of Squids Games game shows and the terrible working conditions associated with them (1) (2) speak to a contradiction in Squid Game itself? Does the marketing surrounding the Hunger Games movies undermine the books’ points about exploitation and revolution? Is dystopian fiction, as it were, cooked?

I. Dystopian Fiction

Every story – be it an op-ed or a short story about a robot president – attempts to sculpt our model of truth: what is and what should be. That model then determines what we do in reality. Science fiction makes its arguments through metaphor, by hyperbolizing real life conditions into unbelievable spaces. It gives us a new angle to view truth; it tests our models in new and strange environments.

The dystopian Torment Nexus, then, is the central device of this heightened reality through which the dystopia models truth.

Take our infamous Game of Squids. The “Torment Nexus” here is a battle royale game where poor people kill each other for money. It’s a very simple model of class struggle in South Korea. The story’s main argument is that working people are pitted against each other for the gain and entertainment of wealthy capitalists. It literally beats you over the head with this point.

So how could anyone miss that point so severely as to manifest the Nexus in real life, exactly replicating the injustice that the show portrayed?

Some say this is a failure of the genre. The purpose of a system is what it does — Squid Game is a product, and its status as a for-profit “cultural phenomenon” results in exploitation for the sake of profit. Despite its anti-exploitation ethos as a work of art, we must regard profit as its primary purpose, and, therefore, exploitation.

So, as a dystopia, does Squid Game fail? Does the creation of the Torment Nexus represent a failure of the story Don’t Create the Torment Nexus?

Or… is there another way to look at it?

A similar thing can be said for a similarly-hamfisted story of worker alienation: Severance. I’ve personally been plagued by Lumon-themed Ziprecruiter ads on YouTube. The ads assume the voice of the show’s evil, murderous corporate giant, its Torment Incorporated, in order to incentivize you to apply to jobs. Like, hey. Hey. What are we doing, man?

Well… we’re doing exactly what Severance said we would do.

Severance makes the argument that corporations use propaganda and unreality to exploit workers. I would argue, then, that its points are not, in fact, undermined by the fact that the property has been digested into that very same kind of propaganda. Instead, it proves the thesis. In my opinion, the Lumon Ziprecruiter ad is Severance’s coup-de-grace. It proves that the show’s dark parody is, 100%, on its face, real and accurate to life. This is what’s happening. The actual product of Severance as a story is simply then an accurate model of reality.

Behind the scenes of the real life Squids Games, the reality described in the original show is manifestly true. Is that not, then, a testament to the original’s critique? Its dystopian metaphor is completely accurate.

If it wasn’t Squid Game spinoffs, it would be Hunger Games spinoffs. If it wasn’t Lumon Ziprecruiter ads, it would be the ten thousand other awful gimmick job site ads offering you the chance to beg to work for a company that will leech away your labor, your drive, and your time on Earth.

Both stories say, “This is how things are.” Do they fail for being right?

II. Black Mirror or Some Shit

My first dystopia, and my favorite, is The Hunger Games. The Games are the work’s Torment Nexus, Katniss the hero readers yearn to be. It’s fun to imagine yourself in this Nexus. Take a UQuiz – what District are you from?1

The key to understanding why The Hunger Games is good is understanding its follower in the 2010s dystopia craze. Divergent has all of the same trappings as Hunger Games. It hits all of the same melodramatic beats: “begins and ends in a peaceful state, focuses on the perspective of an infantryman or grunt, its compelling characters are often found in ‘virtuous victims, scared, usually young, beleaguered, endangered, defined by suffering6, and emotional deaths made in service of the story’s goal: relatedly, the idea that a death during war is anything but ‘in vain.’” It invites the audience into a gamified, Hogwartshouse society. But, although it follows the same form of dystopia as The Hunger Games, Divergent, crucially, is bad.

Divergent’s Torment Nexus doesn’t really operate in service of a point. It’s a bad argument (distinct from a wrong one), a bad contribution to the discourse, and therefore a bad story. It’s maybe about eugenics? It’s maybe about authoritarianism, but not really? It’s mostly about feeling like The Hunger Games.

But it doesn’t. The thing is, although the first book in The Hunger Games is plausibly melodramatic and rompy, the rest of the series is explicitly concerned with breaking any illusions you as a reader might’ve had about this Nexus. It hammers home many, many times that the suffering and death of innocents is meaningless and avoidable, that the main character can keep nothing she gains, that she has almost no agency and exists as a tool of a violent system. As much as The Hunger Games invites you to put yourself into the adventure, Catching Fire and Mockingjay hammer home that you do not fucking want to be Katniss. This model is a horror. And if that wasn’t enough, the author comes back many years later with A Song of Songbirds and Snakes to beat American readers over the head with the fact that they are absolutely not from any of the Districts, but from the Capitol. It doesn’t follow the comforting arc of a melodrama. Taken as a whole, the series is as clear in its dystopian aims as it is possible to be, as pointed as a rapier.

We come to the movies. Again: whatever point the books made about blood spectacle, about capital and empire, about exploitation, the movies and marketing enacted without a shred of irony. Don’t think about your position as a resident of the imperial core watching children die for your profit on television – buy makeup. Buy Subway sandwich. Subway sandwich is your taste of revolution. Who are you rooting for, Gale or Peeta? Who are you betting on? What form of suffering do you want to playact?

Whatever The Hunger Games said the Capitol did, Americans did. We made ourselves up like them. We lived vicariously through blood sport, like them. We defanged every piece of political art, turned it into fashion and status, like them.

Ouroboros!

Ultimately, it’s the same story. Suzanne Collins presented a comprehensive critique. America responded by continuing to act out the system she was critiquing.

Maybe it’s ignorance. Maybe it’s willful misinterpretation. Maybe it’s a failure of the story. Or maybe… maybe The Hunger Games, Squid Game, and Severance simply held up a mirror. And maybe people were okay with what they saw.

The thing is that, once we expand the Torment Nexus beyond hard tech to social systems, we must acknowledge that every Torment Nexus story is written within the Torment Nexus, and then fed back into it. The fact that capital eats every story that points out the realities of capitalism isn’t a bug – it’s the whole point.

And so, as to the author’s liability: If I notice you’re holding a poison apple and tell you it’s poison, you’re going to die, and you say, I don’t care, and then you keep eating it and keep poisoning yourself and even start talking about how the fact that it’s poison makes you enjoy it more, is that my bad?

Alright, then it’s all futile. What’s the point of these stories? What’s the point of telling you the apple is poison? Well, it’s the same point there is in all fiction, the same point there was in protesting the Vietnam war. Even if we don’t fix the problem, even if our art doesn’t cause people to take up arms in the streets – and hey, who knows, maybe it will – there is value in saying, this is how it is. This is what we’re living in. Knowledge is the foundation of action. To plan for a better future, we must understand the present; in order to think about saving ourselves from the poison, we must first agree that it’s there.

Sometimes it’s better to stare the Torment Nexus in the face than pretend we’re not living in the kind of world that would build it.

III. The Right Hand of Light

We discussed the premise, the gimmick, and the melodrama of The Hunger Games. Now we need to discuss the end.

Mockingjay culminates with Katniss’s choice to end the cycle of violence and death despite the unimaginable losses she’s suffered. In the epilogue, it’s revealed that she has children, despite the fact that she’s spent the whole series insisting that she doesn’t want to bring children into the world she inhabits. But now, she has chosen to; for the first time, she has enough hope in the future to trust it with a new generation.

Her children play on what used to be a battlefield. The series ends on this image, something new rising from the ashes of the old order.

The word utopia is sourced from Thomas More’s 1516 work laying out an ideal society. Wikipedia – yes, I’m citing Wikipedia, let me cook – has only one joint article for utopian and dystopian fiction. It defines the two as counterparts:

Utopian fiction portrays a setting that agrees with the author’s ethos, having various attributes of another reality intended to appeal to readers. Dystopian fiction offers the opposite: the portrayal of a setting that completely disagrees with the author’s ethos.

This definition vexes me. The world would be good if I thought it was good, and it would be bad if I thought it was bad. It seems so simplistic as to be ridiculous. Like –

– and yet I continue to return to it.

It’s not incompatible with all I’ve said about dystopia as metaphor. Both utopia and dystopia extrapolate upon a set of real conditions as a way to comment on those conditions. However, I think there’s a crucial difference here. “Here’s how things could be better” is more forward-facing than “here’s how things could get worse.” Dystopia is a warning, utopia a proposal.

My favorite piece of utopian fiction is Star Trek: The Original Series. Many people consider Deep Space Nine to have the most cutting-edge politics in the franchise. I disagree for quite a few reasons – not the least of which being that DS9 completely fails to stick the landing – but the most important is that, to me, TOS is far and away the most politically interesting installment in the series. In-universe, it envisions a future where humanity is governed by principles of unity and exploration, where all people are provided for, where life is valued. It asserts that racism, sexism, xenophobia, and capitalism will soon be things of the past. Many episodes take clumsily direct shots at political issues contemporary to the production of the show. It asks viewers to envision a better future and asks them further what they would do with one.

And the thing is – it fails! constantly! to meet modern or even contemporary standards of progressivism. It’s frequently misogynistic, racist, xenophobic, blindly pro-american. Yet the purpose of the show is not to express a view of what is – except in the sense of human nature – but a vision of what can be. It highlights the good of the contemporary moment and asks, what if we let these seeds grow?

TOS says, in the future, we can be better than this. Even TOS itself is not better than this. But it asks you to imagine that it can be.

Isn’t that an argument against Torment Nexuses, then, you ask? Isn’t this what sci-fi should be doing – envisioning a better world than the one we live in, challenging us to attain it?

But we haven’t gotten to the thing that makes TOS my favorite utopia. It’s one of those details that pops up randomly in the show, changes everything about the canon, and then barely gets mentioned again. It’s that between the 1960s and the Star Trek future, TOS places World War III. Humanity didn’t just Progress from the contemporary 1960s to the diverse space utopia. 1960s TOS looks forward instead to a horrific, bloody reckoning with fascism and eugenics.

Without this detail, the show would, to me, ring far more hollow. TOS isn’t just vapidly proselytizing about a better future. It may get much worse before we achieve utopia, it says. But we can make it through. And we can build something better.

Another piece of utopian fiction that I recently loved is Ursula K. Le Guin’s The Dispossessed. There’s so much to be said about this book and I’m not going to say it all here. Still, I have to bring it up. The story revolves around two societies on two orbiting planets, one similar to modern-day America, the other founded by anarchist dissenters. The book is full of discussion not only of the practical concerns of anarchism and the friction of human nature within it, but of the pitfalls of capitalism, as seen from the outside. The utopia experiences all its growing pains in direct relation to the dystopia it left behind, literally orbiting it. Neither society can be fully understood without understanding the other. Each hangs in the other’s sky.

Late in the story, it’s revealed that humans – real life humans, not the sort-of-aliens we’ve been following (Hainish Cycle is weird) – destroyed ourselves and the Earth long ago. That’s the final piece, the final point of comparison: utopia, dystopia, and complete annihilation.

To quote another of Le Guin’s books: “Light is the left hand of darkness and darkness the right hand of light.” Dystopian fiction and utopian fiction are not at odds. They ask the same question, compose two halves of the same answer. This is not a matter of opposing genres, but of extremes on one axis. Utopia only exists in the context of dystopia. The reverse is also true.

The unified genre can be called neither utopian nor dystopian fiction. We’re left with topos – stories of place, which fall on an axis between utopian and dystopian. Most lean one way or the other. But what do you get when a story tries to be both?

IV. Yuuup… Marxism

Octavia Butler’s Parable of the Sower is an early installment in the canon of YA dystopia from before YA was really a thing. Beginning in the year 2025 in a walled, middle class neighborhood in Los Angeles2, it follows Lauren Olamina, a teenager struggling to survive the collapse of late-stage capitalism.

After her neighborhood is destroyed, Lauren embarks on a perilous journey North, facing the widespread effects of climate change3, racist and sexist violence4, and the enforcement of “company towns,” made legal by a fascist president5, which operate in a system of indentured servitude that evokes Civil War-era slavery. In the course of her travels, Lauren develops her own system of thought, called Earthseed, and begins to gather people around her through a unified vision of individual and collective – conceiving of a new social order as she wanders through the ashes of the old one.

Jonathan Scott’s paper Octavia Butler and the Base for American Socialism is an extremely detailed analysis, and I highly recommend reading it. The main thrust is that, in Parable of the Sower, Butler expands upon the extant conditions of capitalism in order to highlight and analyze the problems she sees in the world… and then proposes a solution.

From the cited essay:

Allen reasoned that if the bourgeoisie was able to overthrow the feudal order “only because their mode of production had developed in the womb of the old order,” then “the basis of the necessary socialist relationship of production must be defined and developed within the womb of the capitalist order before the gravediggers of capitalism can become the builders of socialist society.” His question followed directly: “But precisely how is that relation of production to be defined?”

Butler takes a swing at defining it. Within the crumbling shell of the capitalist order, Lauren – and through her, Butler6 – preconceives a new form of society, free of hierarchy, and then systematically confronts the material problems of making it a reality, including gathering people, building support, and surviving the death throes of the old order.

In this way, Parable of the Sower’s narrative centers upon the exact point of transition from dystopia to utopia. It examines the problems of the real world, then proposes a new way forward; it asks the question, then starts building toward an answer.

In the narrative, though, these things happen simultaneously. There is no clean divide between Parable of the Sower’s dystopian and utopian modes. Instead, it’s a synthesis. It struggles with itself, constantly thrusting toward something greater.

On a broad level, I’d argue that all revolution stories, from Star Wars7 to Black Sails, occupy this position. They plant themselves on the inflection point between criticism of the real and realization of the ideal8.

V. Sidebar: But Where do the Zombies Fit Into This?

Well, you say, that model of topia is all well and good, but what about one of the major flavors of dystopia that Zeke discusses? None of this applies to zombie fiction, where, he says, “The entire framing of the genre encourages us to see others as heedless knaves, getting what they deserve, while preppers, the ultra-violent, and the Daryls finally get to inherit the Earth.” Egads! Where’s the preconceptive value in that? Zombie fiction holds up no mirror, cautions us against no worsening conditions.

Well… that’s because zombie stories aren’t really dystopian. They’re utopian.

Think about it. Zombie apocalypse narratives put forth a vision of a new society after the collapse of the current one. It’s most often an alpha-male-individualist society – but, look, I didn’t say utopian imaginings of the future had to be good. The writer of the ultraviolet zombie doomsday story is preconceiving in their own way. They posit that this, the kingdom of Neegans and The Governors ruling their castles with iron fists, is how humanity will arrange itself next. That this is the value system we will next subscribe to, this the model of strength.

Maybe the stories say vaguely that it’s bad for these men to be despots, but the way to beat them is still by outgunning them. In this world, might makes right, and you have free reign to gun down the faceless hoards scratching at your castle door as you see fit. Sure sounds like “a setting that agrees with the author’s ethos, having various attributes of another reality intended to appeal to readers.”

Therefore, the dystopia itself has already happened. Modern medicine, bioweapons, scientific research, et cetera, whatever caused the outbreak – that’s the actual Torment Nexus. The zombies are only a faceless enemy. The inflection point, then, the actual breakdown of the dystopia, is the moment the first zombie is infected. The post-zombie world then gives the characters authority to arrange their world as they see fit, so long as they have the firepower to back themselves up. The Walking Dead is utopian fiction. It’s about the project of society-building.

There are, of course, actual dystopian zombie stories. In these, though, the dystopia does not lie in the actual existence of zombies, but rather in the hierarchies humans establish after the apocalypse occurs. For example, in The Last of Us, zombies are little more than an environmental threat, and the characters mainly struggle against authoritarian human organizations. Colson Whitehead’s Zone One does a similar thing, and also explicitly addresses the dehumanization of zombies as a bigoted fantasy by drawing a comparison to the real-life dehumanization of Black people.

M.R. Carey’s The Girl with All the Gifts takes this concept to its limit. Here, the zombie apocalypse began years before the plot takes place, and a sort of authoritarian equilibrium was established in the aftermath. As in Zone One, this regime collapses. Then… something new.

See, The Girl with All the Gifts tackles the dehumanization of zombies head-on. In it, the children of zombies are sapient. They’re not human, but not dehumanizeable; they represent a new kind of people. The book concludes with its sole surviving human character accepting that the time of humans has ended, and deciding to pass humanity’s knowledge on to the zombie children. We end with the hope that a new society will rise from the ashes, a synthesis between humanity and the lifecycle of the mind-altering fungus.

Basically, The Girl With All the Gifts goes from dystopian (pre-apocalypse) to utopian in the traditional zombie story sense (post-apocalypse) to dystopian (establishment and collapse of military authoritarianism) to utopian again (conception of the new society). Like Parable of the Sower, The Girl with All the Gifts places itself at that transition point from dystopian to utopian fiction – shaking off the vestiges of the past, envisioning a new and transformed future.

VI. Return to the Torment Nexus

But let’s return to the questions at hand. What actually makes a dystopian story successful (not monetarily, but in merit)? How do we interpret the dystopian stories we have? Is Squid Game good?

For me, Squid Game’s success as a piece of fiction remains to be seen. Squid Game might start with a strong premise and robust dystopian ethos, but later seasons might devolve into a vapid adventure narrative without anything else to say. Alternatively, it could move through the collapse of its dystopia into a utopian vision9, or it could end completely without hope – even if all of the characters die and the Games continue on forever, grinding poor people into the rich’s meat, the point will be made.

And the real-life spinoffs will go on, and the merch will be sold, and people will die in poverty the world over for the aggrandizement of the imperial core. And the point will be made.

And the next killing game story will come along, and the next, and the next, and we’ll eat it up. The people who love to make Torment Nexuses will eat up the Torment Nexus stories and spit out shinier incarnations of the same old hells. And the point will be made.

Until maybe, one day, we stop.

What do stories like this really achieve? Probably not revolution. Proclaiming loudly in the town square that millions are dying for the profit of the few, that genocide is wrong, that ceaseless growth will kill the planet, probably also won’t get you a revolution. It’ll most likely get you fired.

But through the telling, through stories and arguments and protest, we establish that the Torment Nexus exists. We establish that this is the shape of things, and that such a shape is wrong, cruel in the abstract as it is in the real, hostile to human life. There is value in the truth. There is value in saying, “This is what’s happening to us. Look at it.”

Only then can we fully answer the questions of dystopia and utopia:

What is it now, and what can it be?

I smile through gritted teeth.

I’m not saying Butler agreed with everything Lauren believes, but that the narrative is about this preconception and about juxtaposing Lauren’s philosophies with the capitalist ethos that has led her world to its current state.

Lol.

Lol.

Lol.

Lol.

You WILL watch Andor. Right now.

God, yes, I hear myself. I’m sorry. There’s nothing I can do.

Although I doubt the show will end with the complete collapse of capitalism in South Korea, the show could reach a similar conclusion within the microcosm – the game, the metaphor – it has created